Born in 1994, An Simin is a photographer from Jerusalem’s ultra-Orthodox neighborhood of Mea Shearim, known as the home of one of the oldest and strictest Haredi Jew communities in the city. An left her neighborhood at the age of 14 and enrolled in University. She is currently based in Berlin and Tel Aviv.

The first time I met An was around 6 months ago, in a small cafe situated in Kreuzberg, Berlin. She was wearing a pair of plain, black trousers and a puffer jacket of the same color, a silver earring in one ear suited her short hair—from her looks, I would have never imagined her story to be what it turned out to be, which left me quite surprised.

In Japan, the chance of coming in contact with ultra-Orthodox Jewish people is extremely rare. I had never seen them nor was I aware of their existence up until the time I went on a trip to New York as a student, got lost, and ended up in Williamsburg by mistake. That is why, at first, I found myself hesitating to ask An about her cultural heritage. Ignorant of the subject, I was filled with nothing but curiosity, which made me feel as though my questions would sound insincere. When I revealed how I felt to her, she answered: “Don’t worry about it. I don’t know anything about Japan, so I’m really interested as well.”

After that, as we sipped cappuccino, we started talking about our lives for hours. I later asked her for an interview, where she revealed her genuine doubts towards the ultra-Orthodox Jewish society, its absolutistic rules, and how it defined her approach to photography.

No telephone, TV, or computer at home

An is now 25 years old, making her part of what we now know as the Digital Native generation. However, ultra-Orthodox communities usually do not allow visiting the internet, and her case wasn’t an exception.

“It took me 10 years to become a ‘normal’ person since I had no telephone, TV, or computer at home. The internet is a great tool to inform yourself of what goes around the world, but most ultra-Orthodox people still neglect it. There are definitely more people using smartphones, but I think most people wouldn’t own a computer.”

“Escaping from a closed-off community is incredibly hard,” she continues.

“I started using the internet when I was 17. That’s also when I started using social media. I didn’t know anything about the world, I couldn’t even speak English, so it was an important experience for me. I met a lot of people on the internet who helped me countless times, and I also got to see many different photos.”

Photography was like therapy to me

In ultra-Orthodox communities taking pictures is forbidden in most cases, therefore, photography is hardly seen in daily life.

The first time An saw a photo was in a small library in Jerusalem, where she found an issue of Dazed magazine. Her career started soon after that when she found her mother’s old film camera and started taking pictures.

“My mother was 18 when she moved from her hometown in Iran to London and started working as a photographer. But I’ve never seen any of her photographs: when she turned 25, she converted to Judaism and burned all of her photos.”

An left her home and community at the age of 14. “There is still a lot of ill feeling between me and my mother,” she said. “Last year, I invited my mother to my graduate exhibition, but she didn’t come. Maybe she sees her past self in me since she used to take pictures too.”

Her relationship with her mother wasn’t the only sacrifice An had to make to pursue her career in photography.

“When I left my community, I felt as if I was losing myself. It’s because I was brought up believing that everyone exists for the sake of their community, carrying out their duty towards it. So my life felt like it broke into pieces, and by taking pictures I was trying to bring those back together. It was like some kind of therapy for me.”

I thought that when I’d grown older I would put on trousers and become a man

The subject of An’s photographs often regards sexuality and gender.

“In Jewish education, they don’t teach children about their bodies. I am part of a triplet of two sisters and a brother, and when we were younger I didn’t understand the difference between us sisters and our brother. I thought that our clothes were just different: women wear skirts and men wear trousers. That’s because of how strict the dress code in these communities is, so I thought that when I’d grow older I would put on trousers and become a man. Actually, I guess I understood gender fluidity from back then.”

“I used to go to an all-girls school as a child, and they would only teach me how to be a good wife and mother. There weren’t any common subjects like Maths or English, and the only book we had was the Bible.”

Most people in ultra-Orthodox communities get married fairly young, around 17-18 years old for women. After marriage, women shave their heads and wear wigs, and look after their children. An grew up surrounded by women of said communities, always feeling a sense of discomfort. She didn’t think that the kind of lifestyle they had would fit her at all and felt like the only “outsider” in her own community.

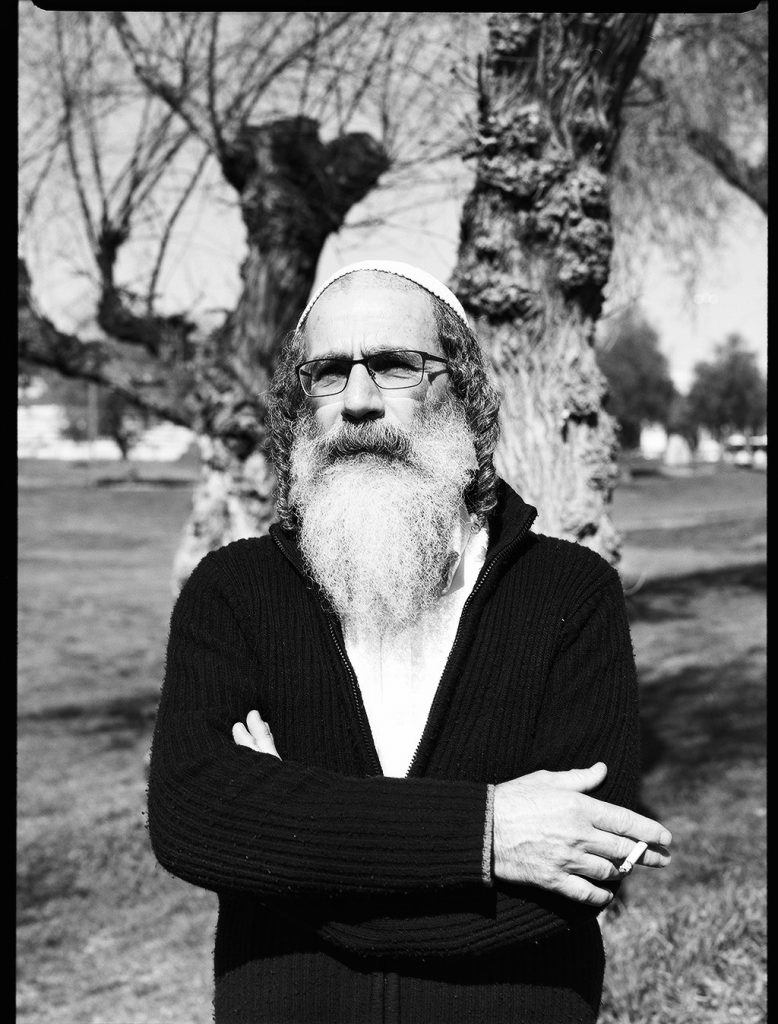

In the middle of the interview, An showed me a picture of one of her childhood friends.

“I took this picture the day after she had a baby boy. She ran away from her husband and started raising her kids all alone. In this picture, she looked sad but beautiful at the same time. Her stiff smile, wig, clothes, and even her makeup represent the traits of an ultra-Orthodox woman. That was the only time she let me take a picture of her.”

“No one speaks about gender in ultra-Orthodox communities. There are, of course, sexual minorities as well, but they are confused: even if they have doubts about their sexuality, they couldn’t talk about it to anyone. That’s why I see photography as a platform to question those issues. I still have many doubts about myself and the community I grew up in, and now, through photography, I am searching for answers.”

The young people of Israel

“Nowadays’ young people of Israel mostly come from families with a ‘modern’ way of thinking, but in a conservative place such as Jerusalem, they still keep their traditional way of life. People have only started abandoning their religion recently, so atheist communities are still pretty small.” An then showed me a picture of a small girl wearing gloves and holding a cigarette.

“I have been taking her pictures for the last 4 years. Her father is also Jewish, but with a little more progressive way of thinking. He lets her do whatever she wants. When I was taking this picture, she was wearing gloves and smoking, but her father didn’t say anything. Before her, I’d never met a child with that kind of lifestyle. Back then, she looked like some sort of ‘Angel of Freedom.’ She could go anywhere and do anything, and I thought that was beautiful, her life being the exact opposite of mine.”

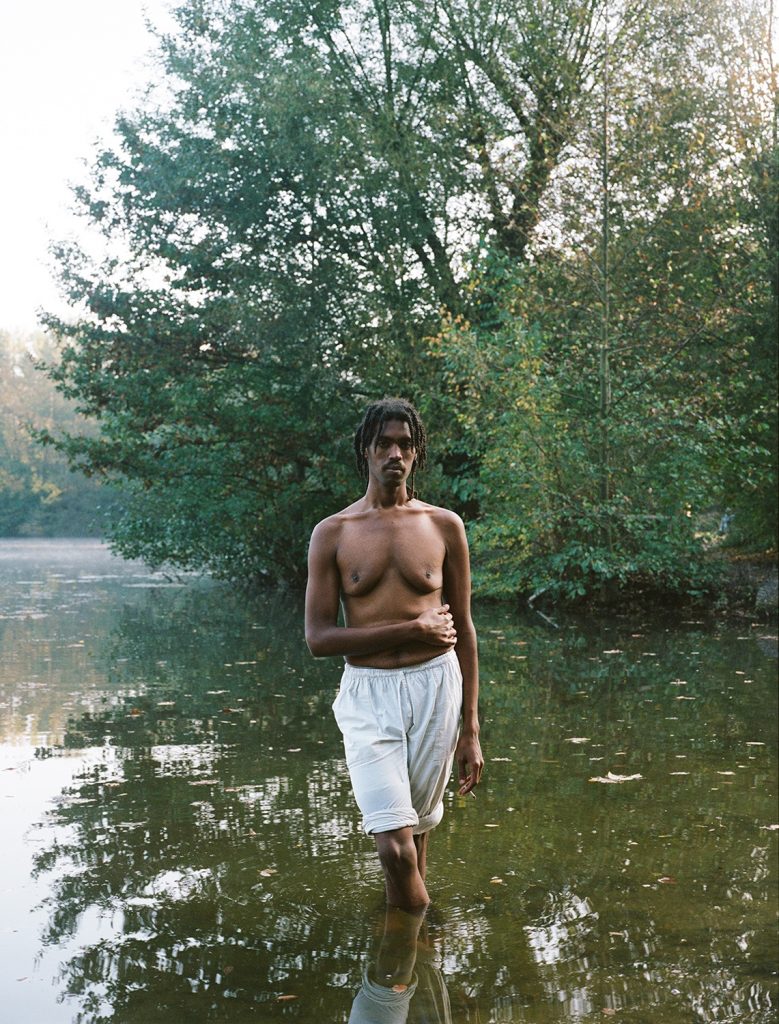

Some months ago, An had met a boy by the name of Idan, who was also from Tel Aviv, but who had lived his life with a completely different set of values than her. Still in his teenage years, his hair was dyed red and he was publicly gay.

“He is also very modern-minded. I took a picture of him as a symbol of modern Tel Aviv. In Israel, the devout Jewish communities and the people living a modern lifestyle co-exist, but they have no way of connecting to each other. That is why I thought that I had to show this to people. Jewish ceremonies and gay nightlife are both parts of Israel.”

The state of ultra-Orthodox communities under the corona pandemic

Currently, the spread of the coronavirus is feared by ultra-Orthodox communities all over the world. In March, The New York Times stated that the percentage of ultra-Orthodox patients in American hospitals is around 40-60%, despite only constituting 12% of the whole US population. Under this global pandemic, receiving accurate information is crucial to surviving, therefore raising the dilemma of ultra-Orthodox communities who refuse to use the internet.

At the end of the interview, An showed me her most recent pictures, photographs of a synagogue, which on further inspection displayed a crooked sign sealing the entrance.

“This is the synagogue in front of my mother’s house. Fearing the spread of the virus, the police have put the place on lockdown, which started a protest against it by the community. I took this picture the day after the insurrection. Most people in ultra-Orthodox communities have no access to the internet, making them unaware of how dangerous the virus can be, so they start going against the police.”

It is important to consider how the current situation could permanently change the state of these communities, which may be forced to adjust their traditional lifestyles. “It’s really crazy,” An continues. “It feels like I became a journalist or something, even though I have only taken pictures for myself.”