Kosuke Nagata, as an artist, has focused on the elements that form the basis of human perception, such as media technology and systems of perception. In his video work “Translation Zone” (2019) presented at the Aichi Triennale, he examines language and food culture from a translation perspective. He connected the creation of “cuisine that doesn’t belong to anywhere” when making foods from one’s own culture in an inadequate environment, with the situation where translation fails or gets mixed up in the process of translating one language into another, and presented these as a kind of richness. For Nagata, what is the significance of rethinking culinary culture?

A couple’s chat, the Malaysianized Hong Kong cuisine, and the intersection of the “culinary triangle”

Personally, I’ve grown tired of the bleak vibe of 2020, and was more interested in topics such as ambiguity, indivisibility, and gray areas. In this context, the “Translation Zone,” which I saw at “Echoes of Monologues” (@ANOMALY) was very thought-provoking—showing the difficulty of mixing and dividing cultures from the popular perspective of cooking. This work was presented at the Aichi Triennale. Could you tell us about the background and inspiration behind your idea?

The curator of the Aichi Triennale, Meruro Washida, offered me the opportunity to exhibit my work, but I had a completely different plan at first. “Translation Zone” is a work based on narration, like a visualized essay, but this was the first time I had created this type of work. The idea came to me when I traveled to Singapore to see an exhibition at the beginning of 2019.

Singapore is a multiethnic country consisting mostly of Chinese people and then 30% Malays, Indians, etc.—and they are quite mixed in terms of culinary culture. I like to eat and cook, so I used to eat at hawkers, a kind of Singaporean food court. One night, I walked into a Hong Kong restaurant, and there was a couple sitting next to me. Somehow, as I listened to their conversation, they went from talking about their families in Mandarin (I think), to suddenly starting to talk about their schoolwork in English.

In Singapore, there are language classes for each ethnic group up to high school, but the common education is in English. If you wanted to take advanced classes in the language of any of the given ethnic groups, you’d need to go to a university outside of Singapore. I knew to some extent that people change their language depending on what they are talking about and who they are talking with, but I was surprised to see it firsthand. At home, you may speak with your family in Mandarin (or in some cases, your parent’s specific local dialect), and TV programs are broadcast in Chinese, but since university classes would be in English, your academic knowledge would be organized in English. Perhaps your first language is Mandarin, but it’s better to speak in English depending on the vocabulary you need.

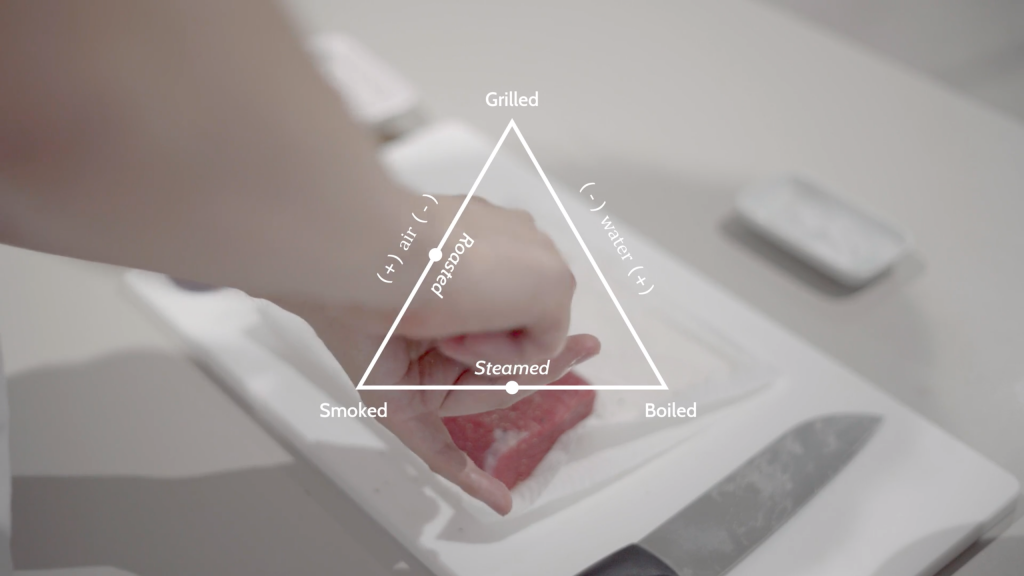

At the same time, the Hong Kong food I ate there was also quite Malaysianized, and instead of Chinese chili oil, I was served “sambal,” a spicy seasoning made from fermented shrimp mixed with hot peppers. I wondered if the mixture of what I was eating and the language of the couple next to me were strongly connected in some essential way. This thought was the main impetus for this work. As I refer to in the work, there is a difficult essay by Claude Lévi-Strauss called “The Culinary Triangle.” This essay was inspired by Roman Jakobson’s study of the vowel-consonant triangle in linguistics, and through my experience in Singapore, I realized that the philosophical thoughts expressed in these essays are very real.

To be honest, I thought I had a theoretical understanding of the ideas presented in “Culinary Triangle,” but somewhere in my mind I thought it was just a conceptual game. I myself often end up thinking abstractly when I create my works, but this time I wanted to start thinking from concrete facts such as the Malaysianization of Hong Kong cuisine and the mixing of languages.

I had always liked cooking, and I had been doing a lot of research on it personally, not necessarily for my artwork, and I was struggling with the gap between what I liked and what I wanted to create, so I thought this might work and made a lot of changes to my initial plan.

How did you end tackling the investigation?

My research was primarily literary, along with a visit to Singapore. I referred to social networking services and online articles for my research on Google Translate and Cookpad. Also, I’m currently living in Yokohama, and about 60% of the stores in the nearest shopping arcade are Chinese, 20% are Korean, and the remaining 20% are so-called Japanese shopping arcade stores. When I buy an item, the conversation about the change comes back to me in Chinese. This is not research, but I think some of my daily life experiences are reflected in my work.

Did the food on your own table change as a result of this environment?

It definitely did. I’ve always liked to eat new things, and to know that such tastes exist in the world. I also like “strange foods”, as they are sometimes called, or perhaps I should say that I find it interesting that there are people who think these foods aren’t strange at all. That’s why I don’t like the word “strange.” It’s true that there are times when I feel uncomfortable eating some things, but I am thrilled by the fact that there is a culture where these things are naturally incorporated into the cuisine.

By experiencing and making unknown flavors, there is a sense that a kind of system of different food culture is partially installed in my body, and I like that feeling. When I first started living in Yokohama, I used to go to the shopping district and look up unfamiliar seasonings on Google Translate and try to use them. I still do that now.

Doubts of Authenticity Arise in Examining Culinary Culture

“Translation Zone” is a video work and can only be viewed at the exhibition. I know that your interest in culinary culture itself is the basis for this work, but for those who have not seen it, can you tell us again what kind of reasoning and motivation you had for creating it?

It’s partly because I like to eat and cook, but I am also interested in how food culture has been created throughout history. More specifically, I’m interested in the idea of “proper food culture.” In traditional cultures, there is often the idea that there is an “authentic culture” and that anything outside of it is a fake. Of course, respect for tradition is important, but that tradition may have been created through unorthodoxy sometime in the past, or it may have been arbitrarily decided upon by someone else.

The stereotypical Japanese dishes are usually sushi, tempura, and sukiyaki, but these were not always eaten in the same form as they are today. Modern sushi is the result of the transformation of “narezushi”, originally a preserved food, into a fast food. Sukiyaki was born from the normalization of eating beef after the Meiji era (1868-1912), and the current form of sukiyaki did not take root until the early Showa era (1926-1989). Tempura was established in the Edo period, but it came from Portugal, right?

In this way, the dishes that are considered authentic in Japan today were created by simplifying or modifying traditional foods, or by bringing in cooking methods and ingredients from abroad. When we think about food culture, we realize that no matter how authentic it is, it has not always existed unchanged since ancient times, but has been created through various changes.

This led me to think that through cuisine, we can broadly examine the idea of cultural legitimacy and the conservatism and exclusiveness that comes with it.

Why did you think that Singapore would be an appropriate stage to reconsider these issues?

I thought this was a very unique case in thinking about national and ethnic identity. Japan is considered to be a mono-ethnic nation, and “Japanese” as a race, ethnicity, or nationality tends to be strongly identified with. It may even be said that some Japanese believe that there is a pure “Japan” and that there is a clear boundary between it and the surrounding culture.

Singapore, on the other hand, is a multi-ethnic country with a history of only about 60 years since its founding. Chinese, Malaysian, and Indian cultures are mixed together, and it is often said that there is no culture unique to Singapore, and that their common language, English, is called Singlish, or even Broken English. In reality, however, I believe that such cultural mixtures are the process of creating culture and language.

Rather than having a pure “Japanese culture” or “Chinese culture” first, and then mixing them to produce impure versions, I think that such cultures are more like “deviations” that emerge from a place where various local cultures are mixed together. Even traditional Japanese culture was created by such a process, and is still in the process of being created anew.

The title “Translation Zone” comes from the work of Emily Apter, a scholar of comparative literature, who takes as her starting point the idea of the thinker Walter Benjamin that translation is always “in translation.” Apter’s “translation zone” is imagined as a kind of linguistic buffer zone where translation does not belong to a single language or media, but is always a mixture of multiple languages and media. Such zones are not limited to language alone. I would say that Singapore’s food culture is truly a translation zone of multiple food cultures.

More so, such translation is probably taking place in everyday cooking. By cooking with what is available in the refrigerator or substituting ingredients that are not on hand, we end up with dishes that combine elements of multiple cultural and regional origins. I thought that in such cultural mixtures, the seed of a new food culture could be seen.

Actively disarming the internalized norms of “proper eating habits”

In today’s world, where division and differences are often emphasized, what do you think is the significance of looking at the difficulty and ambiguity of dividing cultures using cuisine as an entry point?

I think life, not just cooking, is something that we have to manage on a daily basis, so there is no room for political positions or ideologies. We can’t live without food, and since it is connected to physiological pleasure, I feel that for many people, especially in Japan, food has become like a truce line in their ideology.

Food is a place where ingredients and cooking methods of various geographical and ethnic origins are mixed together, and at the same time, it is a place where global food distribution networks and local industries overlap. I would like to think of the starting point as a state where various things are unavoidably mixed. I feel that such a state of affairs is more fundamental than the idea of a clearly divided nation-state, and I believe that such a state of affairs is at the very least a source of cultural richness.

What takes priority at the table are personal considerations, such as taste, convenience, and the ability to use leftover food from the refrigerator, and not the concept of national circumstance or divisions.

When issues of nation or ethnicity are involved, suddenly large and rough subject terms like “Japan is” or “Japanese are” are often used. Perhaps there are situations where such easy-to-understand and organized divisions are necessary when talking on a large scale. However, I think that the origins of the things that are talked about in such a large subject and the origins of the things that make up our lives are probably completely different.

Of course, even in our personal eating habits, there are norms for “proper eating habits” that are introduced by educational systems such as school lunches and home economics, and by media such as home cookbooks and television. Although there are differences between individuals, we have internalized norms such as “this is what eating should be like,” and I would like to break these norms, and I would like to actively affirm the kind of indiscretion in our lives that we inadvertently break due to sloppiness or random thoughts.

I feel that one of the charms of this work is that while the content presented in it is philosophical in nature, it can also be felt practically at the dinner table every day.

Art is often perceived as something extraordinary, and in fact it is full of various leaps and delusions, but I would be happy if people could see it as an extension of everyday things. The meal you cook for yourself every day may not be any different from “Pad Thai made with udon noodles.” I hope it will lead to an experience where the food you eat everyday suddenly seems strange and you can’t help but think about what it is.