Global Art Daily (GAD) is a web and print publication that focuses on the local creative scene in Abu Dhabi, the capital of the United Arab Emirates, and the Arabian Gulf. With the motto “Welcome to the (rest of the) world,” the magazine’s founder/editor-in-chief, Sophie Arni, describes GAD as “a place born to encourage dialogue between different cultures.” Having multiple cultural experiences, from Europe to Abu Dhabi to Japan, we asked her about the origins of the art scene in the Arabian Gulf and the meaning of “global” in today’s world where the pandemic has spread all over and borders are closed.

A discussion space for a new generation making up the global, nomadic, and polycentric art world.

First of all, could you tell us about the beginning of GAD?

I started Global Art Daily (GAD) when I was in my second year of university at NYU Abu Dhabi. I had just moved to Abu Dhabi two years prior and started my undergraduate studies in Art History. I was fascinated by the term “global art.”

The university gave me an opportunity to study art history from a variety of perspectives, and I learned about contemporary Arab art, the European Renaissance, the history of photography in America, Mono-ha in Japan, and Ming Dynasty porcelain in China. I learned that “global art” is not a new concept. We can just look at the heritage of the Silk Roads, the exchanges inside the Persian and Mughal empires, Marco Polo and the Portuguese conquests, and the British and Dutch East India Company to see that artists, craftsmen, and curators moved across borders throughout history, and created artworks that were not necessarily defined by one regional viewpoint. Perhaps the whole history of art is a history of cross-cultural exchange.

Abu Dhabi at that time was bustling with new cultural and museum investments and central to the curatorial premise was the idea of East meets West. Abu Dhabi was situating itself to become a cultural hub in the Middle East, a meeting point between Europe and Asia. The UAE’s leaders understood the power of art and museums to elevate the city’s image but also to establish Abu Dhabi as a place for meaningful cross-cultural dialogues. The Louvre Abu Dhabi, which opened in 2017, and the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, which is currently under construction, are part of a larger movement questioning Eurocentric museology and curation.

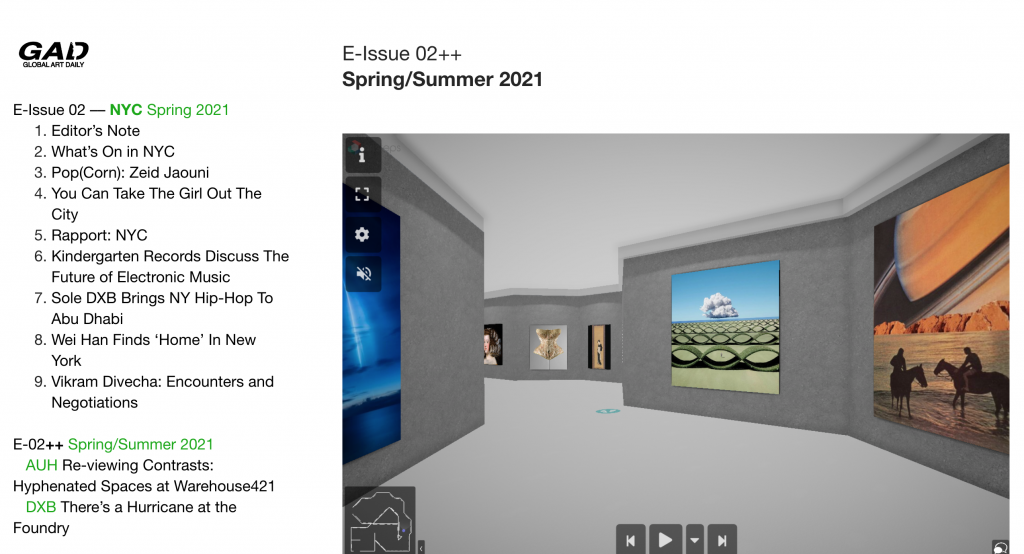

In the context of contemporary art, I believe that “global art” today lives and spreads on the Internet. Works are first distributed and exhibited “physically” for biennales and art fairs, but this is only the beginning of their life cycle. Next comes the “phygital” (physical-meets-digital) experience, which is on the rise, especially with the pandemic: how the work is photographed, the extent to which the image is liked on social media, and how it is re-shared with others.

In terms of cultural exchange, the visibility of dialogue (between both sides, such as twitter replies and instagram comments) has made it more transparent, and many artists are sharing references and inspirations with each other. We are living through an important ideological shift in the cultural sphere, with artists and curators from all corners of the world taking ownership of their local narratives and sharing it to a global audience. I wanted to create a platform to highlight and discuss this new generation making up the global, nomadic, and polycentric art world.

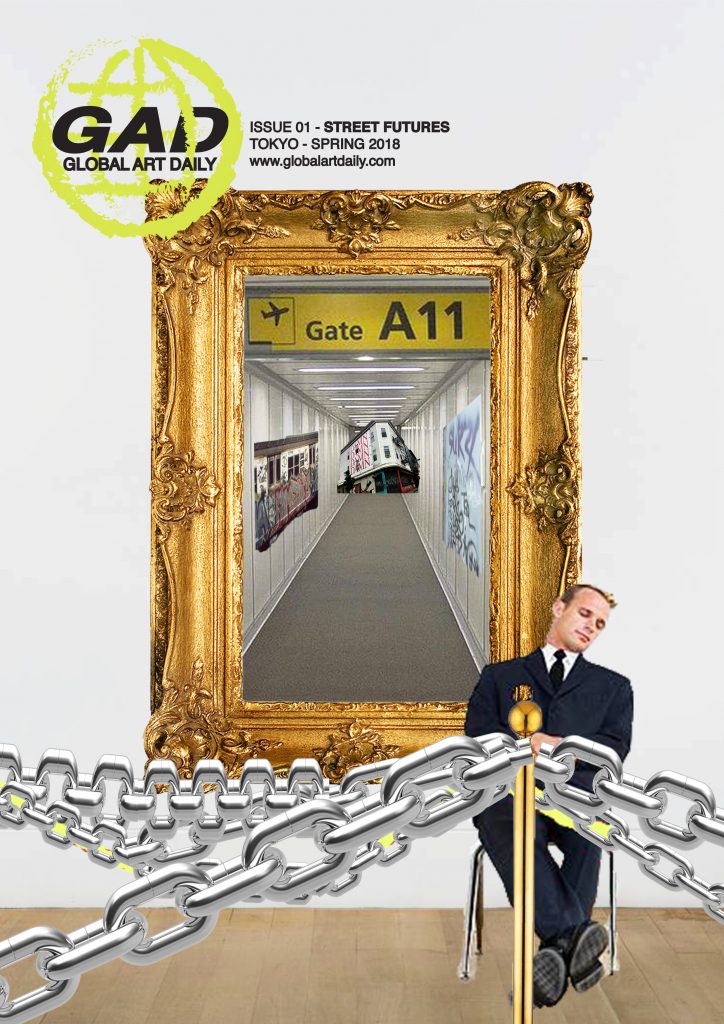

GAD Magazine Issue 01, March 2018, “Street Futures”

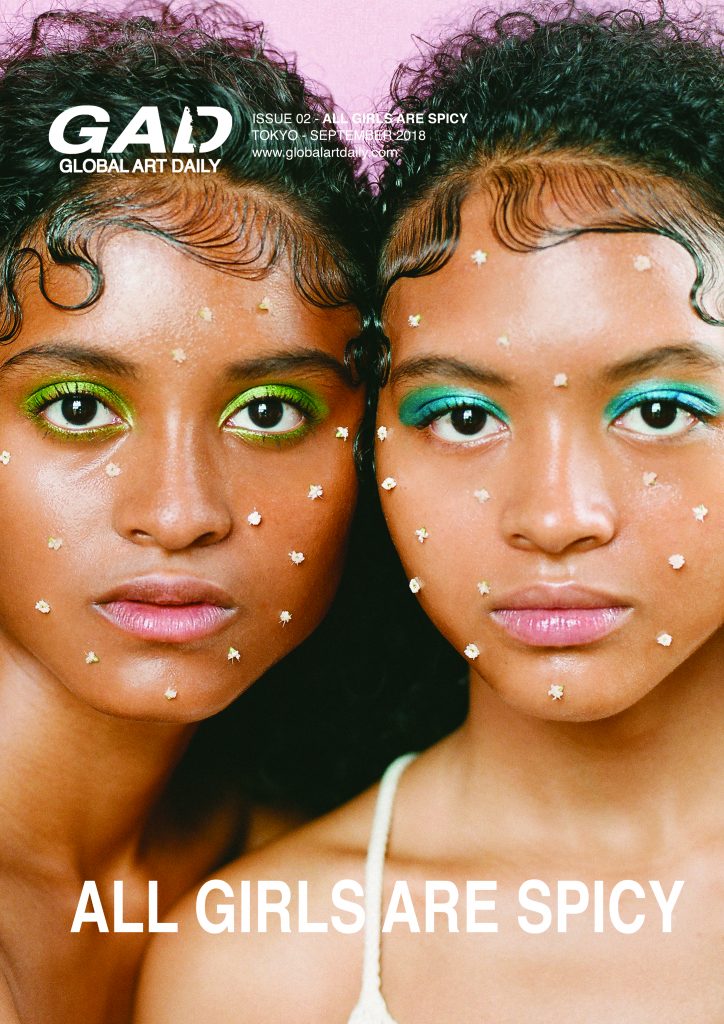

GAD Magazine Issue 02, Spring 2018, “All Girls Are Spicy”

When I sent you a question via email before the interview, you advised me to replace the word “Middle East” with “Arabian Gulf.” Could you please tell me the differences between these?

The word “Middle East” is a somewhat problematic one. First, some might argue that it has colonialist undertones. From the point of view of France or the UK, the Near East is Turkey and West Asia, the Middle East is Pakistan, and the Far East is China, Korea, and Japan, but is it really necessary to keep using the words “East” and “West”? There is no such thing as a “center” where culture is born. There should always be more than one “center.”

The Middle East is a large region, it is difficult to put all these cultures, peoples, and customs into one category. GAD has been focusing on the emerging art scene of the Arabian Gulf, the region consisting of the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar and Oman. These countries are called the GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council). For some context, the Arabian Gulf and the GCC overlap in some countries And (to complicate matters further) “GCC” is also the name of an art collective formed in Dubai.

The limits can increase creativity

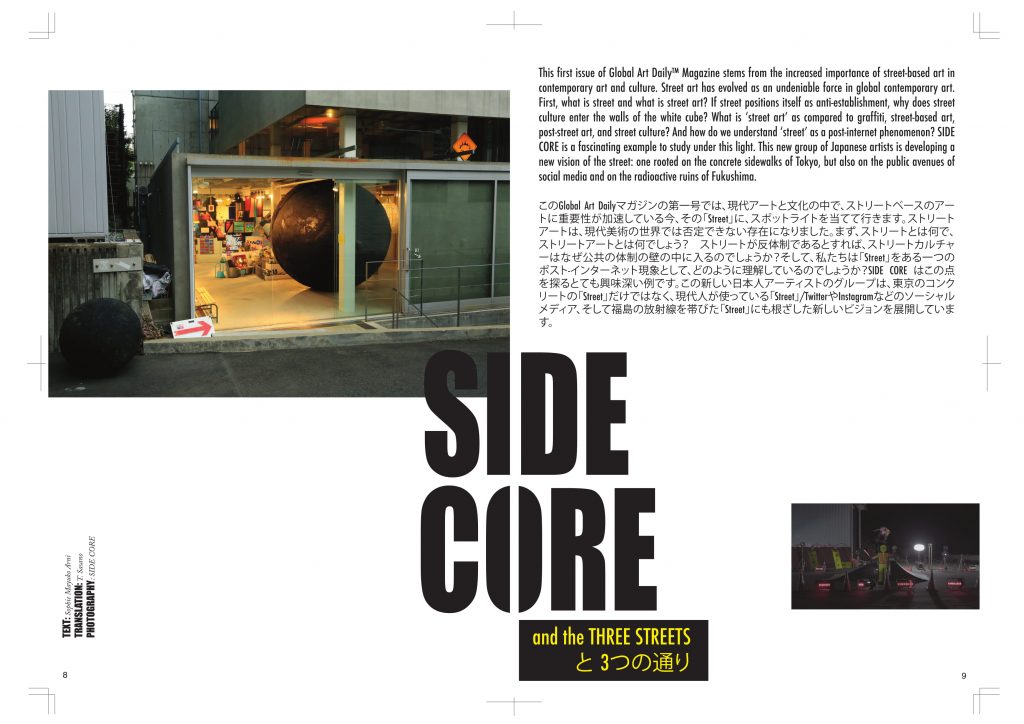

There are murals in public spaces, but they are commissioned by museums or local governments, and as you pointed out, eL Seed’s works can be considered public art. Graffiti is prohibited by law, and if caught, there is a risk of deportation to one’s home country given the UAE’s large immigrant population., This makes it difficult for countercultures to grow. However—the theme of the first issue of GAD was “street art”—I believe that the Japanese art collective SIDE CORE said it the best: “the new street is the Internet.” This is very applicable to the UAE: social media is a huge part of the art scene. Instagram especially is a very big thing.

Artists can instantly publish their critical thoughts on Instagram, and then they can quote, make collages, and create a space for critical debate with their followers. This tends to be more of a discussion around the ideas of pop culture, mainstream news, and local experiences For example, artist and producer Rami Farook posts memes everyday about topics affecting our global consciousness, such as American politics, and also anchors it to the Gulf reality.

We tend to think of Arabian cultures in terms of easy dichotomies, such as “Arab vs. Western.” But when I visited the UAE, I was surprised to find numerous immigrants from non-Arab cultures. People from various cultural backgrounds work together, they speak English when they do business. Is that kind of diversity also reflected in the art? Also, do people who have moved here ever participate in the art scene in the UAE?

In terms of participation in the art scene, I am very happy to see more UAE-based (non Emirati) artists participating in the exhibitions in Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and Sharjah. Not so long ago, the art scene in the UAE was split between “imported” exhibitions by international artists and Arab UAE-based artists. However, at least in the past five years, there has been an increase in the number of non-Emirati, non-Arab, UAE-based artists in gallery and museum exhibitions.

For example, American-born artist, curator and creative director Christopher Benton has lived in the UAE for 10 years and is active in the Dubai art scene. There is also Augustine Paredes, a photographer from the Philippines, also based in Dubai. NYU Abu Dhabi graduates have also been based in the UAE, including Daniel H. Rey, a curator of current interest who is Paraguayan-Colombian.

On the other hand, the UAE is also a country built on transience: citizenship is difficult to obtain, which makes it very easy to get in and out of the country depending on visa validity. However, this situation is now changing. I heard that the government is planning to give artist visas for example, and simplify the process of obtaining citizenship for special immigrant categories.

Augustine Paredes, for example, came to the UAE for a job. But he decided to leave his mark on the city through art. He called this city his “home” and created a place for himself. Whether he stays in the UAE for a long time or not is not so important. He “took up space” through his art practice and is leaving an important mark for future generations after him.

I had an image of the UAE as a region where freedom of expression is restricted due to strict religious norms, but when I visited UAE, there was no stifling as I had imagined, and in fact, the artists seemed to be working freely.

Since the UAE is a Muslim country, there are restrictions on certain subjects to be covered in public exhibitions. However, compared to some other countries I have lived in, I can say that the UAE is a country where it is easy to express one’s thoughts, including on cultural topics. Besides, I also believe that the existence of taboo subjects can help artists and curators to be more creative by working within a certain set of guidelines.

What does it mean to say that limits increase creativity?

For example, Christopher Benton’s piece “LLC FZ CO (A Great Place for Great People to Do Great Work)” is a work that mentions the success stories of migrant workers, which can be considered a sensitive topic in the UAE. Many migrant workers in the UAE come from South Asia, such as India, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan, to work in construction and send money to their families back home. Many of them are single men, known as “bachelors.’. They live in small rooms with bunk beds.

So there are a lot of advertisements on the streets, such as “bachelor wanted,” and Chris made a mash-up of them into a three-dimensional installation. These advertisements are aimed at migrant workers and this aspect is definitely one of the factors that shape the UAE. Chris seems to be both visualizing and celebrating this, while distancing himself from the hyper-localization of the context.

Engaging with contemporary art is a shortcut to developing a deeper cultural, social, and political awareness.

Because GAD focuses on sensitive issues in Arab countries, I imagine it’s important for you to remain independent.

Since we want to talk about global issues, we have always kept GAD as a neutral platform. This is the approach we found most successful for talking freely about art.

Being “global” is a kind of ideal, and we have been through a lot of trial and error before we arrived at our current form. At first, we were covering international exhibitions, but then we decided that there was no point in duplicating information with well-known media, so we focused on young local artists based in Abu Dhabi, and realized that the local had a lot of power. I believe that GAD can amplify and empower local voices around the world, and in doing so, it can become a transcontinental network of artists of a new generation.

At GAD, we interview not only up-and-coming Tokyo artists and curators like Rintaro Fuse, BIEN, and Yuu Takagi (organizer of the art space “The fifth floor”), but also artists like Chris mentioned above, as well as DJs from New York, fashion designers from Manila, filmmakers from Berlin. For me, “global” is not only a geographical word It also means we do not separate the art world as something special, but rather remove the boundaries between categories and look at the creative industry as a whole from a larger perspective.

I always want to be, as a person, as global as possible, with multiple cultural perspectives, but I often find it difficult to remove the fixed point that I have inside myself. That is why I feel that if I don’t keep having dialogues with people from different backgrounds, the “global” in me will disappear before I know it.

In editing GAD, I am always conscious of the need to include contributors and editors who have multiple cultural perspectives. For example people who have grown up in a different country than their home countries, people who have moved between several countries, people who have a strong interest in other cultures, people who have traveled all over the world, and so on. People with these backgrounds do not belong to “one country” in the strict sense of the word.

This is a deeply personal cause. I am half-Swiss, half-Japanese, grew up between the Middle East, Africa, and Eastern Europe, went to university in the United Arab Emirates, and pursued my Master’s in Japan. Not belonging to any ethnic group or feeling part of any nation was very difficult. For a long time, the only thing I wished was to fit in somewhere. To have a simple background, a one-word reality. That’s when I found the word “global,” and my community within Global Art Daily. In the future, I hope to use all my resources and knowledge to advocate for the rights and responsibilities of global citizenship.

With pandemics restricting movement between nations, I feel that the meaning and value of “global” itself is changing.

Yes, it is. At the same time, we feel that online interconnectivity is accelerating. In recent months, GAD has been receiving information from all over the world for digital exhibitions, digital auctions, and digital gallery previews. The digitization of the art world is probably democratizing “global art,” which used to be limited to collectors who could afford to travel the world to attend art fairs and biennales.

The very meaning of the word “global” is changing, and 2020 has seen a rise in nationalistic sentiments around the world. The concept of closed borders is becoming stronger but it is important to keep an open mind in order to live in these times. To truly promote diversity and mutual understanding, we need to tackle topics and issues that are unfamiliar to us. That’s when global thinking comes in. The only way to do this is to be more curious about others than ever before and to keep the dialogue going. We must think everyday about how to become better global citizens, recognizing and respecting the myriad subtle differences that define each culture.

In this sense, engaging with contemporary art is a shortcut to developing a deeper cultural, social, and political awareness. Artists are, first and foremost, “thinkers.” They share their daily struggles, geopolitical research, and personal histories through their work, and we can learn a lot about their communities by being exposed to their stories. That’s why I’m such an ardent supporter of minority representation in all areas of the creative industries. We need to hear every story. We need to hear every perspective. And I hope that “diversity” doesn’t become just another trend.