The first major retrospective exhibition of the art unit Exonemo, “UN-DEAD-LINK,” on view at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography until October 11, gives us an insight into the group’s efforts to “reconnect with Internet art” while looking back on their 24 years of work.

What was your intention in dividing this exhibition between an “internet venue” and an actual venue?

Kensuke Senbo: I had been planning to hold this exhibition for about three years. However, with the outbreak of the coronavirus, it became unclear whether the exhibition would be able to be held, or if it would even be possible to travel to Japan, and we were even thinking about holding it online only. However, the museum thought it would be difficult to hold the exhibition without a physical venue, so we decided to hold it both online and in person. As a result, we ended up with an exhibition that was twice as big as it was at first.

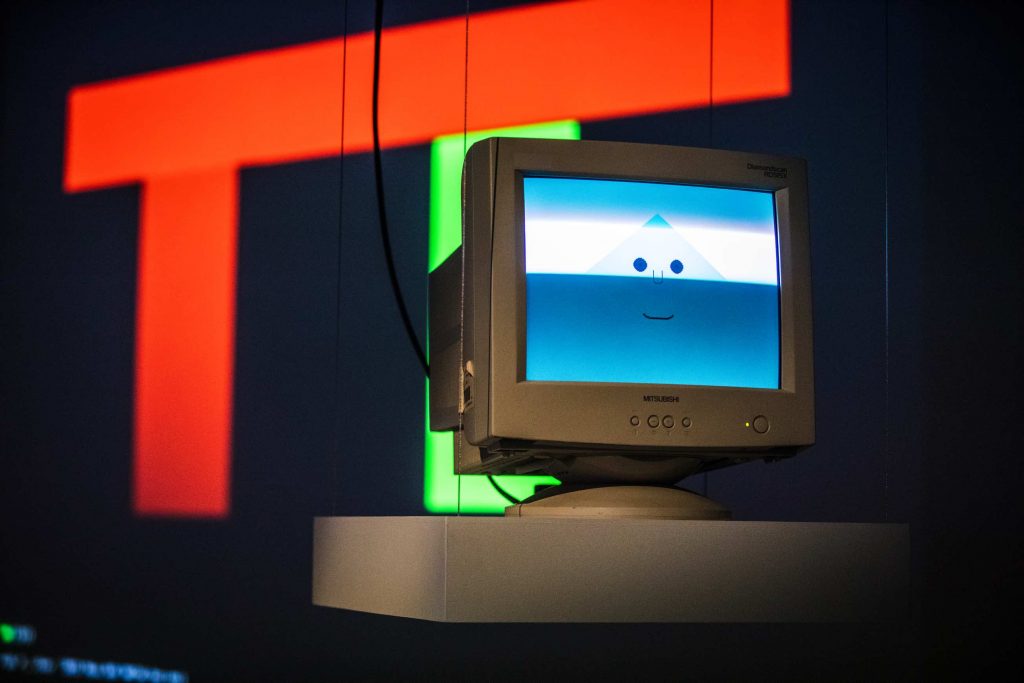

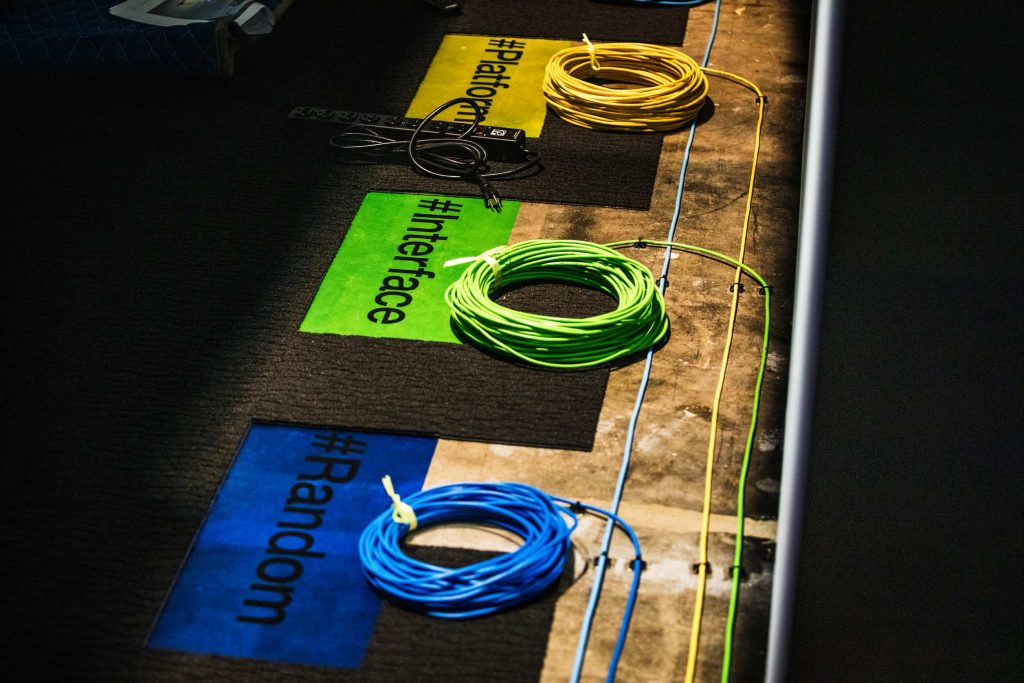

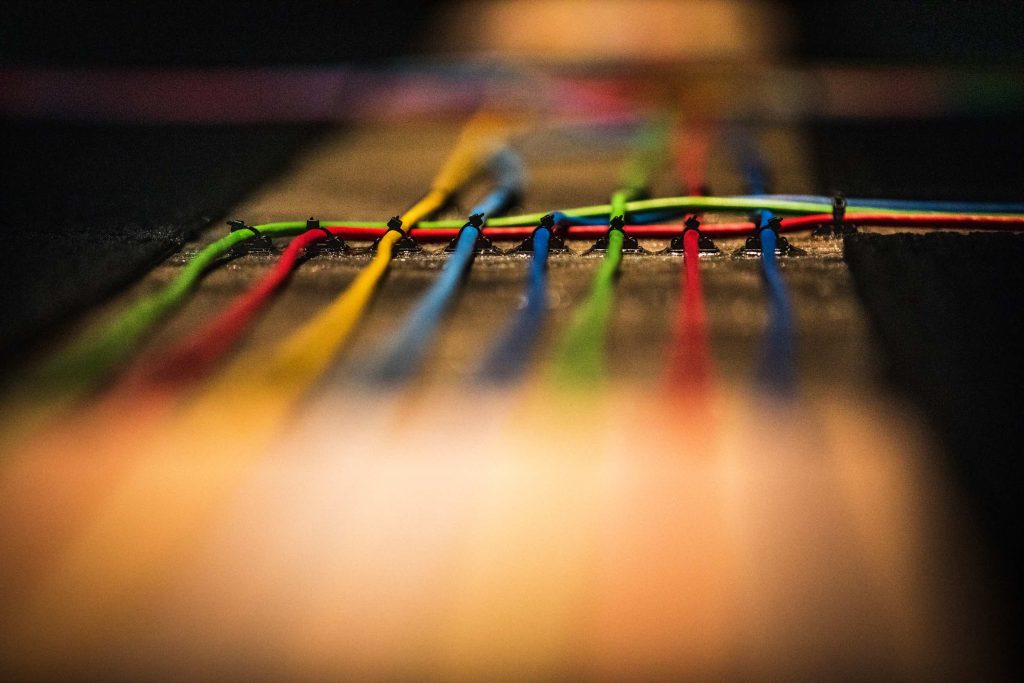

Yae Akaiwa : The Internet exhibition will function as an archive, and we’re preparing to show a timeline of our activities to date, with the goal of eventually capturing them in the museum. In the venue, we prepared 20 works from 1996 to 2020, connected through cables that crawl through time and keywords that decipher the work. There are some of our major pieces in the mix.

Why did you decide to do a retrospective now?

Akaiwa: Actually, I always want to show new works, but the museum really wanted that. Just as we were discussing it and deciding whether to make it a retrospective, by chance Covid-19 started to bring the possibilities of art and expression on the Internet back into focus, and we started to come back to it ourselves. We weren’t too keen on the idea of a “retrospective” to begin with, but we thought it might be a good idea to take this opportunity to look back on ourselves and explore the possibilities of expression on the Internet again, and we gradually got into the swing of things.

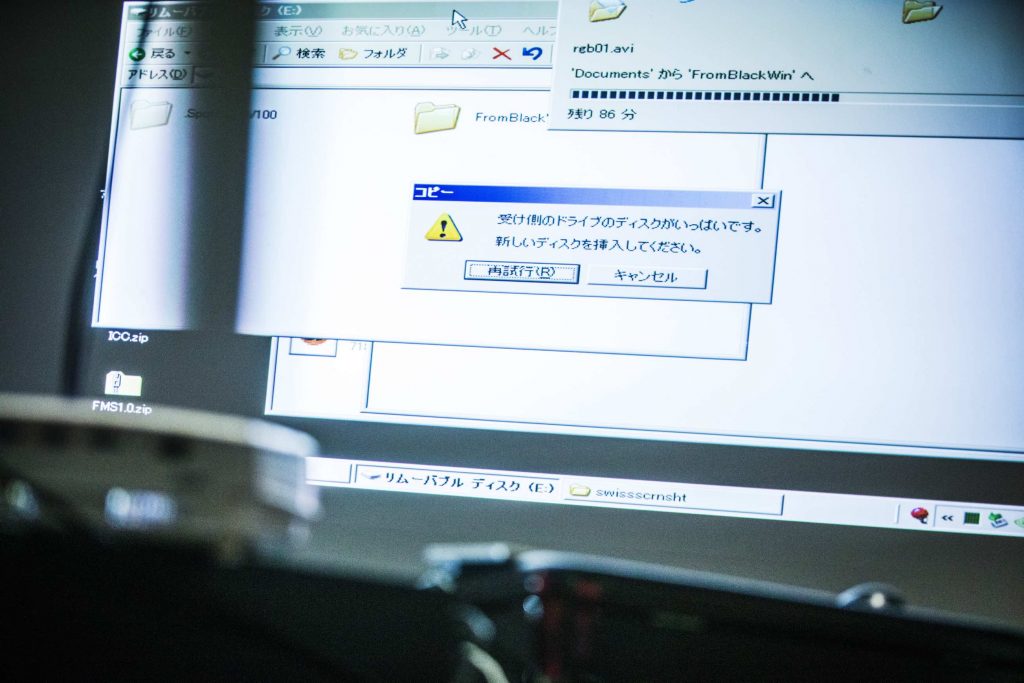

Senbo : The title of this exhibition comes from “UN-DEAD-LINK,” which I exhibited at our solo exhibition in Basel, Switzerland in 2008, and I’ve reworked the work I showed at that show as “UN-DEAD-LINK 2020”.

The word “undead,” with its zombie-like resurrection imagery and feeling, has surfaced as the title of this exhibition in response to the post-lockdown period.

Did the experience of the pandemic in New York have a strong influence on your work?

Akaiwa: It was pretty serious. I really couldn’t leave the house anymore. The only place I could go for a walk during the lockdown was a huge cemetery about five minutes walk from my house, and my new work, Realm, was created through the experience of going there almost every day.

Senbo: There were people around us who were infected and dead, and there were ambulances running around outside our house every day, so it was pretty tense for about three months after the outbreak. That said, we’re probably the least affected artists because we do a lot of internet-based work and work remotely. Of course there have been a lot of cancelled art fairs and exhibitions, but on the other hand, we have received invitations to do projects that involve the internet, and it doesn’t feel like many of them have been rejected. In fact, part of me is excited to see how the world is going to change from here.

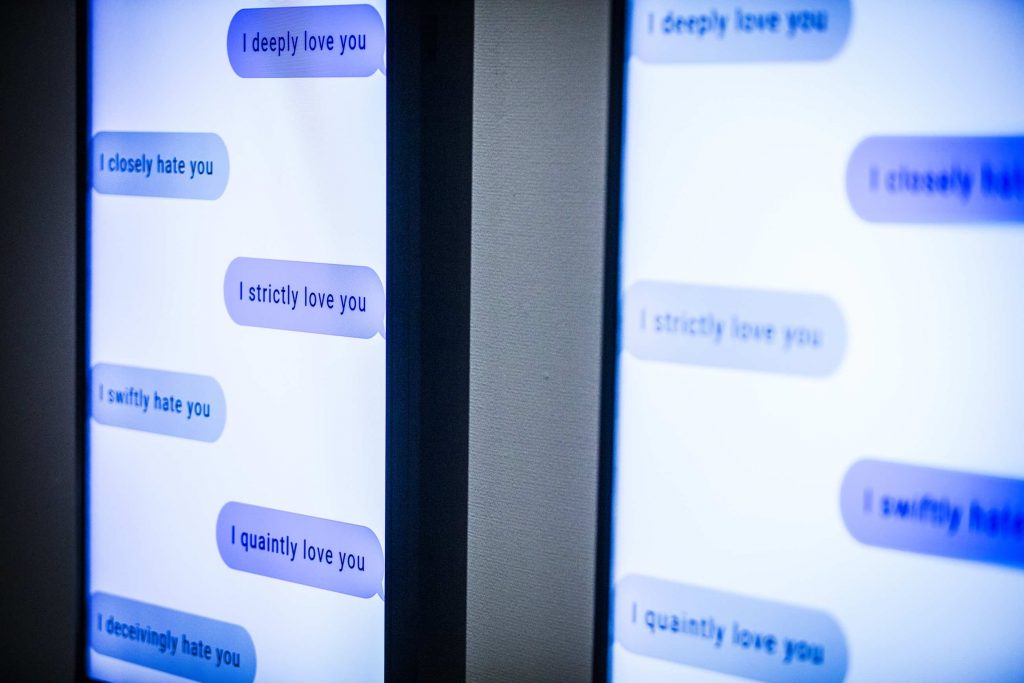

Akaiwa : I’ve always been a bit of an internet person. For example, in terms of how we spend our time online, we’ve tried many different things in the IDPW group* that we run. One of the projects, “World Wide Beer Garden,” was an experiment that connected people in different cities and offices to drink beer online, similar to what is now known as “zoom drinking.” Our “Internet Bedroom” project was an experiment to connect people who are sleeping over the internet to the rest of the world. The Internet is a “daytime” space where people are only active during the day. Our aim was to bring the “night” into this place where we are always connected by day and to relay the act of sleeping. Both of these are based on the idea of bringing the act of real space into the internet.

* a group that conducts experiments using both the Internet and real space. The concept is “a secret society on the Internet that has been going on for 100 years.” Various parties such as “Internet Yami-ichi” are held irregularly.

I’m looking forward to seeing how this exhibition will look to a generation of people who have never experienced a world without the Internet.

Akaiwa: What’s interesting is that school for 11-year-olds has become completely remote learning and they can’t see their friends anymore, and the online communication they have is through games. Online games are now a social place, and your avatar is a part of you. It’s not the same idea as ours of taking things and actions from the real world and bringing them online, but rather creating a new place that is connected to the real world. It’s a completely different approach. On my daughter’s Instagram page, she alternates between the (fictional) nature of her favorite Minecraft game and the (real) nature she’s interacting with in her neighborhood’s lush cemetery.

Senbo: When we were preparing for the game in the Unity (3D development environment) internet venue, we had a child come in to try out the game, and all of a sudden he jumped on my head (in the internet venue) and went flying over the wall, clomping around (laughs). They have a completely different physical sense from us, or perhaps they have an innate sense. I think that these people will make the world of the future.

So I don’t feel like we’re catching up with the times at all, but rather we’re showing the old generation to the people of today and what the Internet used to be like. I’d be happy if people could feel the gap between that and today’s Internet environment, with its large monitors and complicated equipment.