A journey to the land of war, disaster, and other sorrowful memories of humanity—dark tourism. The artist Narco’s research focuses on places and monuments that have been denied in history and intentionally removed from people’s memories.

In 2016, They began researching dark tourism, particularly in Taiwan, and created sculptures of Chiang Kai-shek, a symbol of the dictatorship, with the proposition of “creating contemporary statues of Chiang Kai-shek.” Their solo exhibition “Silent Statues” (Seishukuteki no Chouzo) (2020, TAV Gallery, Tokyo) drew attention for its penetration into a taboo subject in Taiwanese history.

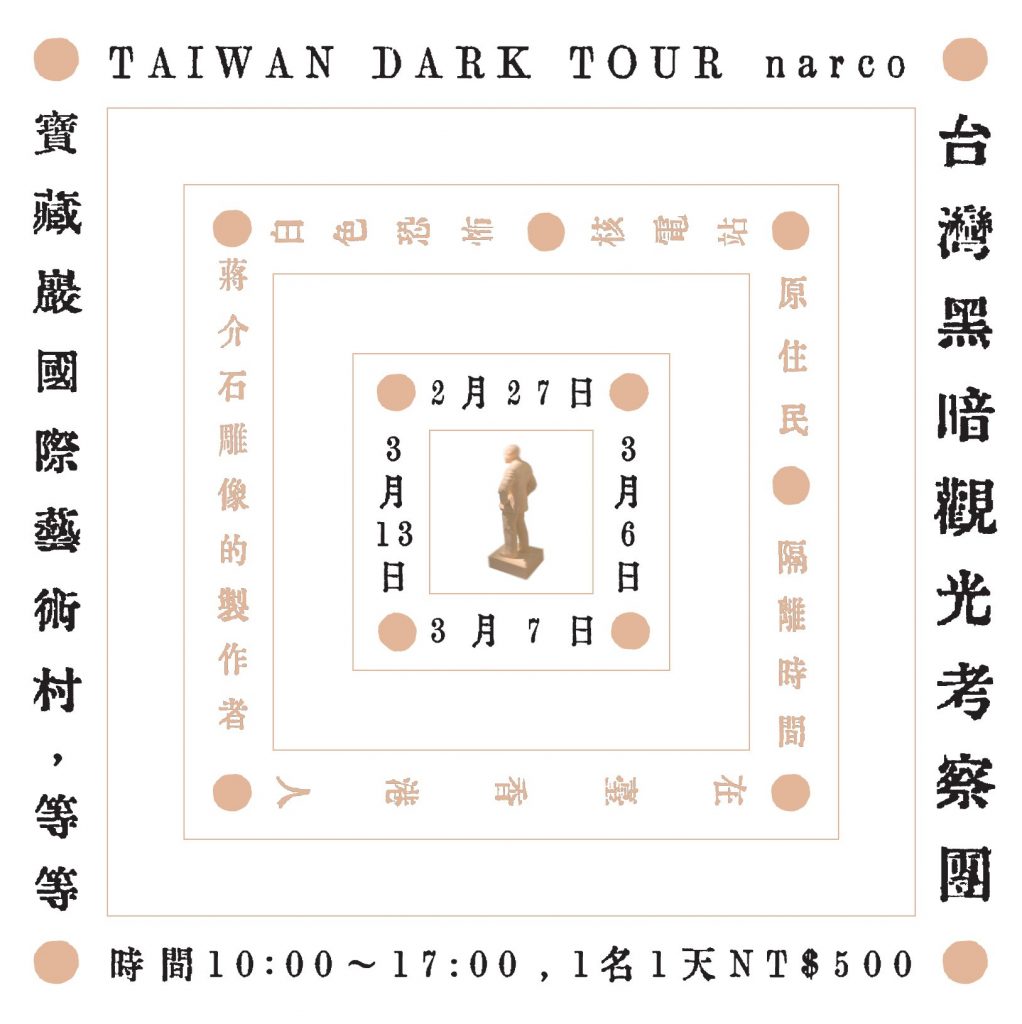

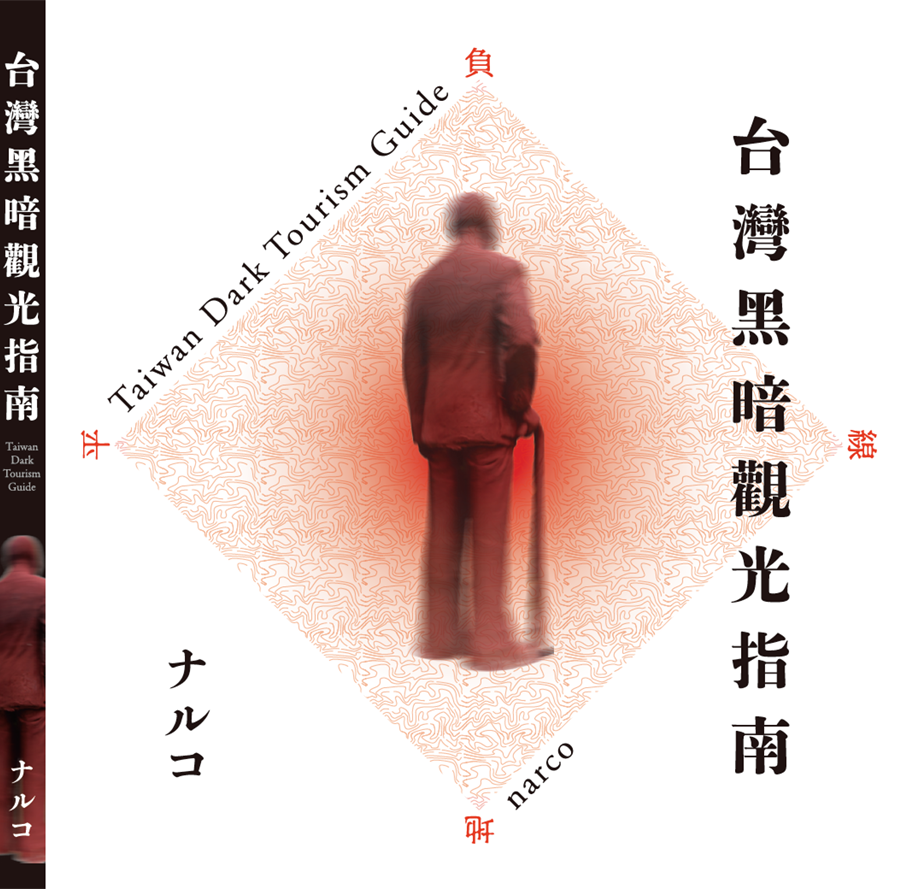

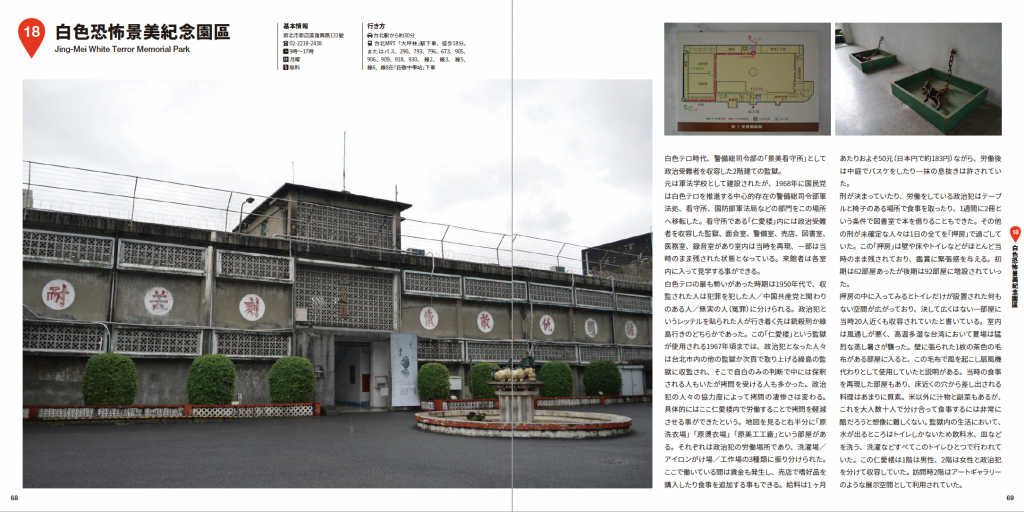

Their four-year research on dark tourism in Taiwan was later published in a book titled Taiwan Dark Tourism Guide (台灣黑暗觀光指南), and they’ll hold a tour in 2021. In the book, they say, “I myself am an ignorant and irresponsible tourist, but that is why I have the freedom to focus on Chiang Kai-shek’s statue and nuclear waste as an entry point to understanding Taiwan.” Why did they decide to delve into the history of another country, Taiwan, in the approach of dark tourism? We spoke with Narco, who is currently in Taiwan for their residency and participation in the Green Island Human Rights Art Festival.

(Top Image: Courtesy by TAV GALLERY/Photography by SAKAI Toru)

Chiang Kai-shek on the verge of death, still unburied and in storage

First of all, could you tell us why dark tourism and why Taiwan?

As for why dark tourism, it has to do with my family history. My father works in the media, and from the time I was a child, I was basically only allowed to watch news programs and weather reports. One day, I had a chance to visit my father’s workplace, and I learned that there was news that wasn’t broadcast on TV. The information in the media is selected by someone, and we get to consume it. This fact really stuck with me as a child. After that, I began to feel uncomfortable with the fact that Japan has elements of history that are inconvenient for it and they don’t dare to leave behind monuments to it—which serve to pass on this history to future generations. I think the starting point was when I started thinking about how I could share this sense of discomfort in a tangible way.

When did you first start using the term “dark tourism” in your work?

I’ve been interested in it since I was a kid, but it wasn’t until 2016, when I went to Taiwan for the first time, that I started using the term “dark tourism.” When I was attending an art prep school, I met some friends who had ties to Taiwan, and they invited me to come visit them. I had always been curious about Chiang Kai-shek’s park (Cihu Memorial Sculpture Park), but at the time, I didn’t have any intention of doing any research , and went there as a tourist.

In the years following the March 11 disaster, I felt that the concept of dark tourism in Japan was considered inappropriate and dangerous as it implied violence against the people affected by the disaster, and I had the impression that the people who had been using the term were drifting away from it. However, after visiting Taiwan, I realized that it is important to pursue dark tourism and started to use it actively.

Is that when you got the idea to make a work around dark tourism in Taiwan?

That’s right. It all started when I visited Chiang Kai-shek’s park (Cihu Memorial Sculpture Park). As soon as I saw the countless statues of Chiang Kai-shek, I was struck by the complexity of the historical background, the future of the statues, and the distance between me, a stranger, and the statue of Chiang Kai-shek. I had a strong intuition that this was something I should work on. It was at this time that I came up with the idea for “Statue on the Verge of Death,” (瀕死の彫像) which was shown in my solo exhibition, and it took about four years to turn it into a work of art.

Chiang Kai-shek’s body is still kept unburied by a method called “embalming”*. Before he died, he left in his will that he wanted to be buried only after he had reclaimed mainland China, so he was not buried and the statue of Chiang Kai-shek was left there for a time. I felt a kind of sick feeling about this situation. The statue is not alive or dead, but the idea “on the verge of death” expresses the fact that the cursed words of his will are still enforced.

*……A technique to prevent decomposition of the body and to preserve it. The circulatory system is used to replace blood with embalming fluid, and the entire body is permeated and fixed.

I found it interesting that the sculptures of the Chiang Kai-shek statue were made of silicone and were pliable. Why did you choose to make it shake when you touch it?

I thought about how to express the “dying” part of the “statue on the verge of death.” Basically, the statue doesn’t move, but I wanted it to shake for a moment when you touch it, as if you were giving it an electric shock using an AED. If the material was soft like slime, the vibrations would continue to tremble like ripples. We had a lot of technical problems to solve, but we kept the “movement” part in mind. The choice of silicon as the material led to the work being seen in the context of “soft sculpture,” which I had not known until the start of the exhibition, and I think it also brought out its appeal as a sculpture in unexpected ways.

I think it was quite bold to create a statue of Chiang Kai-shek with such a strong political context. How was the reception and reaction by the audience?

To be honest, although I was well aware of the risk of creating a statue of Chiang Kai-shek, I thought I would not receive a harmful reaction showing it in Japan. However, there were some cases where I was told that I could not post information about my exhibition on a certain website, and some collectors were hesitant to buy works with a strong political message. On the other hand, what I didn’t expect was that the response from Taiwanese people living in Japan would be so positive. This was just the reaction of those who visited the exhibition venue, but some of them looked at the work as unique and took photos with it.

If this work had been treated as taboo even in Taiwan and recognized as unsuitable for exhibition in a public space, it would have become difficult for you to travel to Taiwan. The fact that you have actually been accepted into a residency seems like their response to your work.

Yes, I agree. This kind of response makes me keenly aware of how different the approach to distancing oneself from political subjects is in Japan and Taiwan. As the issue of the women statue at the Aichi Triennale has shown, there is a strong reaction to works that provoke social and political debate, and a structure on the exhibition side that makes it dangerous to do so. I would like to learn from Taiwan how this relationship can be developed to the point of mutual discussion.

How do you feel about being involved in Taiwan, a politically complex country, as a Japanese outsider and from the perspective of dark tourism?

Not only in Taiwan, but it is difficult for foreign tourists to accept the history of others. Taiwan in particular has a history of being a colony of Japan, but it also has a pervasive image of being a pro-Japanese country. Therefore, I spent my days researching with the awareness that I should not forget the guilt of not knowing how I should feel. On the other hand, I think that forgetting that guilty feeling may be a part of normal tourism. I don’t cover much about the Japanese colonial period in my book, Taiwan Dark Tourism Guide, but that doesn’t mean I have forgotten that history. I basically still feel guilty about it.

Wasn’t it difficult for you to face the work with this sense of guilt?

It may not be the best way to describe it, but I think this guilt is, in a way, like a bulletproof vest that protects your beliefs. I am sure that there are people whose families and people around them suffered terribly during the martial law era who would strongly resist the act of “rebuilding the statue of Chiang Kai-shek,” and there are also people who would be averse to my focusing on the history of Taiwan under martial law (rather than the Japanese colonial period) because of the historical facts of Japan’s colonial rule. Some people may feel guilty if I focus on the history of Taiwan under martial law. I have a feeling that if I were to forget my guilt, these feelings of resistance and disgust would sting me in the flesh and lead me to self-censorship, restricting my activities on the grounds that they are inappropriate. That’s how I feel about it.

So the guilt, in part, functions as a device to drive the work.

To elaborate a bit, for me, this guilt is about trying to understand the psychological distance between myself and the problems that others face, and being aware of past history as my own. The elements that make up guilt are always present, changing their form as we get involved with others and broaden our views.

There are two situations in which you can forget about your guilt: the first is when you stop thinking about it, thinking that it has nothing to do with you right now. The second is when you become so close to the subject that you feel as if you have become a part of it. In order to remember my guilt, I am constantly trying to be aware of my position and the distance between me and the people involved.

A journey where reality is transformed when we return to our daily lives again

As an artist, it is interesting to be a guide for dark tourism. How do you see your tours?

I once participated in a “tour” theater production as a researcher. It might be better to call it a “tour performance” rather than a tour. It was a project to perform a contemporary educational drama using the framework of an existing school trip, and the participants, together with several researchers, discussed the itinerary from the planning stage. By participating as spectators and acting out the gestures of the spectators, the participants learn the purpose of the tour and change the way they see the city that has become their theater.

I came into this project really fresh. I think the perspectives of theater, tourism, and art are all different, but the theory of “learning through performance” in educational theater was just shocking. At the same time, I learned about the aspect of theater that forces us to imagine the relationship and distance between us and the people involved.

Can you delve into that a bit deeper?

At the end of the tour performance, there was a time for discussion with the “people” who live in the city we saw as a theater, and seeing the absolute distance between them and “us,” the performers, I felt the limits of the imagination of the theater. The performers proposed to the people concerned that they could use the characteristics of touring performance to learn by performing in a real city, but since the content was unexpected and difficult for the people concerned to realize, they expressed their confusion. In the end, I don’t think we were able to have a good discussion between the two sides after that. The understanding of the characteristics of tour performance and its potential ended up being a one-way street between the two parties.

When I participated in this project, I had already started researching dark tourism in Taiwan, but I had not yet conceived the idea of making it into a tour. However, from this experience, I began to think about the possibilities of “acting” and “not acting,” as well as the possibility of expression that is neither of these. In order to do so, I decided to first understand “tours” as commercial tourism. By actually working in the tourism and travel industry, I had a hunch that I might be able to express myself in a way that would help me understand the gap between the people who seek travel and tourism, and the structure of the industry that provides it. …… From my experience of providing weekly day bus tours, I believe that the key to the means and process of turning a tour into a work of art is to consider the extent to which the artist has control over the participants (i.e., the artist has initiative over the viewer’s actions). It is a kind of dramaturgy that I am attempting to create.

What does it mean to you to tour in the context of dramaturgy?

The question was, “What would a statue of Chiang Kai-shek look like today?” This is the main theme of the dramaturgy in all of the tours I have organized, including the “Taiwan Dark Tour,” the touch of the Chiang Kai-shek statue in my solo exhibition, and my book, Taiwan Dark Tourism Guide—the tours are the gateway to solving this question.

From the stage of deciding which places to visit, in what order, and for how long, I try to show the intentions and schemes of the dramaturgy in the flow to visitors. The same applies to the order of the table of contents in my book. When I showed this book to people in Taiwan, they immediately understood what I wanted to do just by looking at the table of contents. In the afterword, I specify the targets of dark tourism in Taiwan as “Chiang Kai-shek’s statue” and “nuclear waste,” and I focused on these two in particular in the first half of the table of contents, and then structured it so that the reader can move through Taiwan’s history between the two events, disasters, and history as dark tourism.

What possibilities do you think dark tourism offers to the participants?

This question is related to the raison d’etre of dark tourism. In the popular conception, dark tourism is described as “a journey through memories of grief.” However, when I actually traveled to various countries—and there were indeed horrific events that made me want to look away—I did not feel that I was tracing the memories of sorrow. Rather, I often felt how such events had been protected and tried to be passed on.

For example, in a village in France where the Holocaust occurred during World War II, there were irons and bed frames left as they were, cars left rusting, and whole towns left intact, which had a strong impact on me. But at the same time, when I saw that the lawn in the garden was neatly mowed and kept without a single piece of trash, I was impressed by the fact that there were people who were taking care of this place and that there was a strong will to preserve and pass it on.

Why does this place exist in front of us now? Who has preserved this place? I think the significance of dark tourism is that we can spontaneously become aware of these things. When you come back from your trip, the subject of dark tourism will be reflected in your own daily life. The fact that there are histories and people that have been forgotten or are hard to see will become much more real to you. I believe that the experience of dark tourism can give participants the possibility to change the perspective in front of their eyes.

I used to go to Belfast where there was still conflict between Catholics and Protestants. There, they still closed the gates separating the Protestant and Catholic quarters at five o’clock. At that time, I didn’t know how to react, and could only keep thinking about the bizarre scene itself. In that sense, I feel that there is a lot to be taken and learned from having a “guide” provide a perspective on things. Are there any dark tourism spots that you refer to when you organize your tours?

Minamisanriku Hotel Kanyo in Minamisanriku, which became famous in the town as a hotel that accepted many disaster victims during the earthquake. Employees of the hotel act as storytellers and give bus tours of the remains of the disaster every day. As reconstruction work progresses and it is difficult to see the extent of the damage, we visit the places that remain as the reminders of the earthquake with episodes that only local people can understand. The order in which the spots were visited and the way the story unfolded were helpful for those who compose dramaturgy. While restraining the viewers in the bus, I wondered to what extent I could expand their imagination through storytelling in the details—I think it’s a wonderful initiative that is run by the private sector.

Do you plan to do dark tourism in Taiwan for some time to come?

This year, I plan to work on dark tourism in Taiwan until that art festival. Another thing I’ve actually been researching is Lithuanian dark tourism for about two years now. My reference for dramaturgy is a Lithuanian poet named Czesław Miłosz, and through my research on him, I’m planning a tour on my own. I hope to complete it as a “tour that can be realized whether you go or not. It will probably be a kind of personal experiment to examine the platform of the exhibition itself, similar to the “the horizon refuses to deny or confirm” series that I did in 2017 or so.