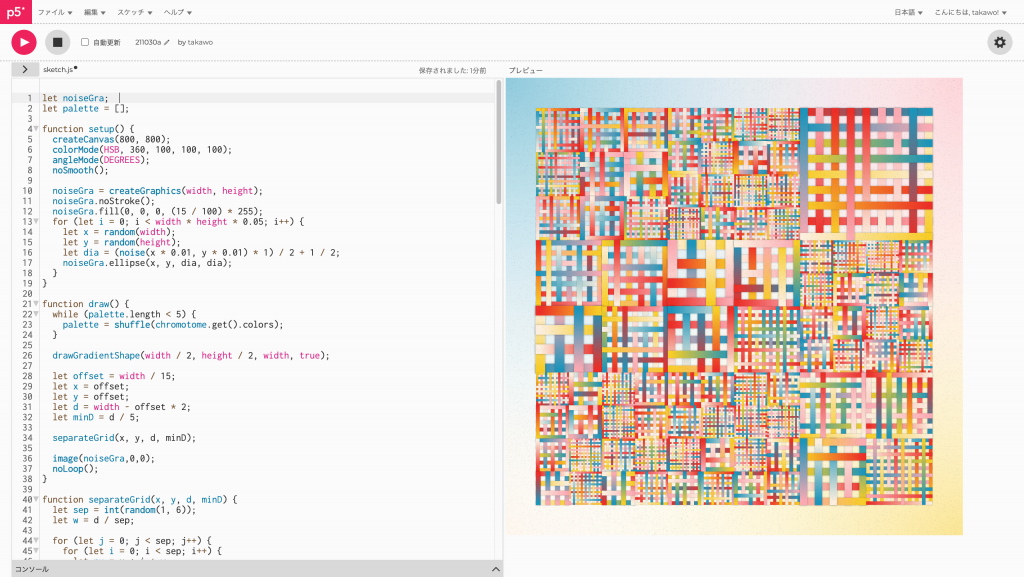

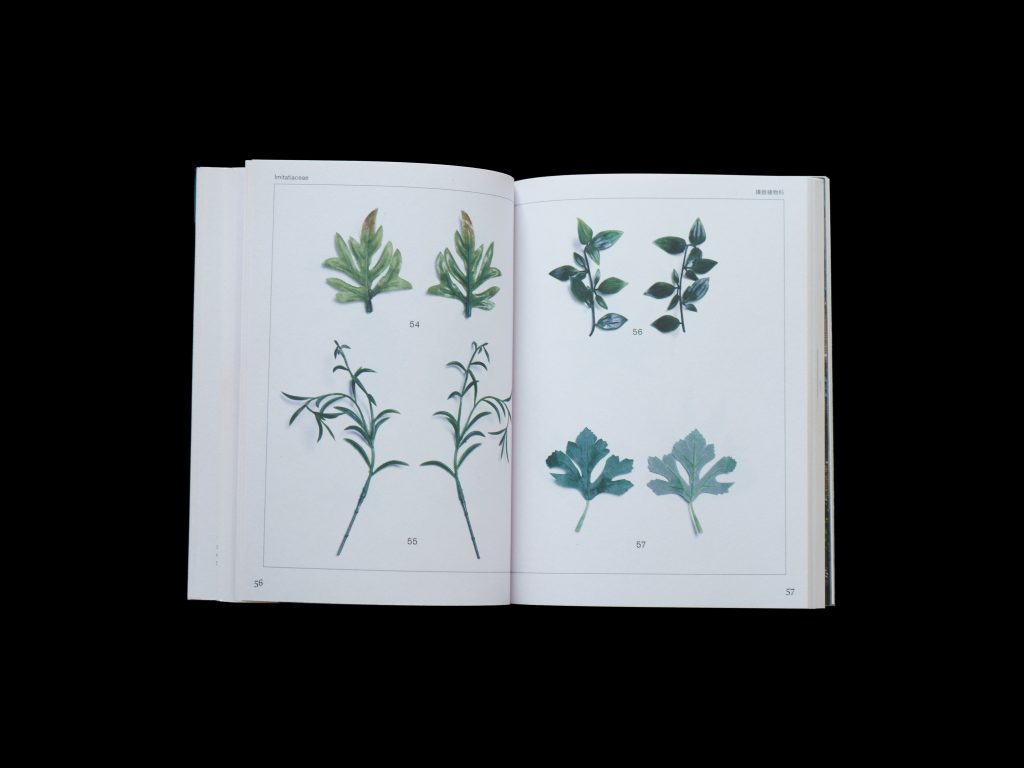

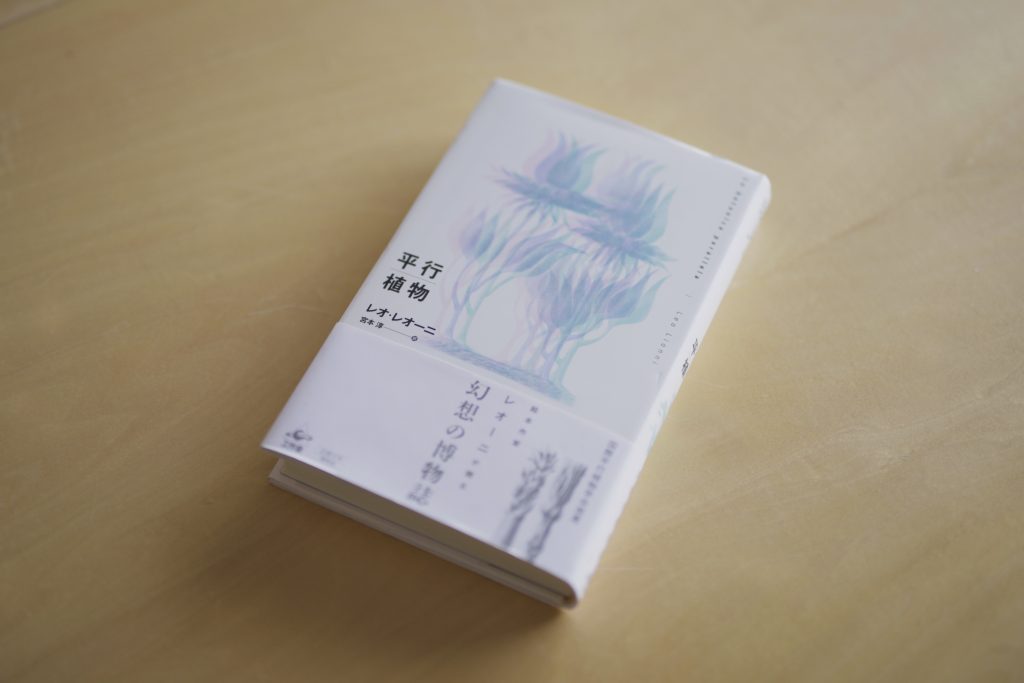

Artificial flowers are now officially recognized as “plants” in botany. Anthropophyta (Torch Press) by Sae Honda, a jewelry artist based in Japan and the Netherlands, is a semi-fictional botanical illustrated book based on such a premise. The title, “Anthropophyta,” is a word coined by Honda as a botanical classification name for artificial flowers. In this work, Honda draws on Leo Leoni’s imaginary natural history, Parallel Botany, and closely observes artificial flowers, which are created by human intentions and do not seek water or light, as an “untouched group of plants.” About 70 leaves collected in various countries were compiled in an academic style.

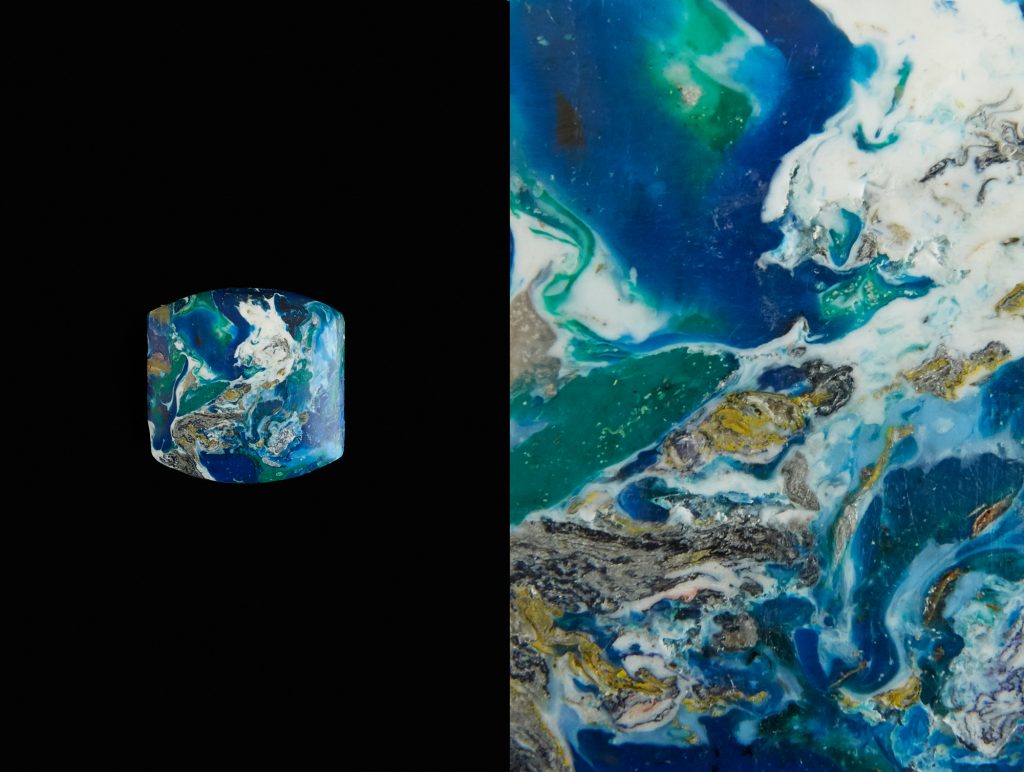

EVERYBODY NEEDS A ROCK is inspired by a new type of stone that is a mixture of plastic waste and natural materials, and Tears of Manmade is a unique update on artificial pearls. In this article, I’ll discuss Honda’s work, background, and production style.

I read your book, “Anthropophyta”. I thought it might be the work of a documentary photographer, but I was surprised to see “jewelry artist” in the profile at the end. Could you tell us a bit about your background?

I originally studied at the jewelry department of the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, where I learned about contemporary jewelry. Contemporary jewelry is an area of art jewelry that focuses on the concept of using materials freely, without being bound by the value of materials such as precious metals and gems used in fine jewelry.

Ever since I was in elementary school, I liked to make things out of used milk cartons and trash in arts and crafts class, and to look for treasures in cheap recycle stores and second-hand stores. I was interested in upcycling designs and how to add value to something that had no value. So I was naturally drawn to the contemporary jewelry movement and decided to go to the Netherlands to study.

It is true that I call myself a “jewelry artist,” but I think I am more of an artist who “thinks about how to value things.” Jewelry has a lot of “value” attached to it, such as monetary value and emotional value, so I often start my work with that form of jewelry as a starting point. That’s why I call myself a “jewelry artist.” I research whatever interests me, and choose the form of presentation that best suits each project.

What did you spend most of your time doing in the Netherlands?

Every year was different. In 2020, I was working on a project of artificial flowers and imitation pearls with the help of a grant for young designers from a Dutch foundation called the “Creative Industries Fund NL.” In Izumi City, Osaka, there are many historic factories that manufacture imitation pearls, where artisans carefully create them one by one, just like a craft.

This “craft of making fakes” is something that is not easily noticed by the world. Since they are fake, their value is naturally lower than that of the real thing, but I wanted to turn the tables on that and created jewelry made of artificial pearls that show their human imperfection.

We are selling them as products. I have been creating artworks as art for a long time, but since I have been working on “value,” I thought that the meaning would change if people could use them in commerce.

photographer: Lonneke van der Palen

Imitation pearls are made by layering layers of pearl coating on a nucleus of beads made of glass or plastic. The nucleus is an imitation of a pearl, so it can be round or shaped like a freshwater pearl, and the coating is layered on top of it, but the shape of the “nucleus” can be anything. We will create an ornament that sparkles like a pearl, but is not a pearl. So, in this project, I tried to create an ornament with a sense of discomfort. “It is as if I am designing pearls themselves.”

In the preface to Anthropophyta you mention that you were inspired by Leo Leoni’s Parallel Botany, but why did you approach artificial plants with the format of an illustrated book?

I think it is important to observe things when finding value in them. It’s been a long time since people started talking about recycling and eco-friendliness, but I can’t help but wonder about the sense being recycled is itself enough to justify its value. There is a tendency for the producers to aggressively promote the value of their products by leaning only on the fact that they were recycled, rather than the fact that the products themselves are beautiful. In such a situation, if we want to add real value to things, it starts with observing them—this is the faint message that is common to the basis of my works.

I was originally a little curious about the existence of artificial flowers, but when I took a closer look at each one, I found that the human errors that occur in the process of mass production, such as misprinting and misaligned leaf veins, appeared as the character of the plants, making them look like living things. Just as there is diversity in plants, there is also diversity in artificial things due to the parts that humans cannot control. I thought that by compiling the ecology of these artificial plants into an illustrated book as a semi-fictional story, I could convey this interest in a simple way.

When did you start collecting artificial flowers?

I started doing this a little bit in 2018 or so. If you keep an eye out for them, you’ll be surprised to find them laying here and there. In the Netherlands, artificial flowers are often placed on graves and fall to the ground, so I have been collecting them for over a year.

I’m sure you get some strange looks.

That’s right. Especially at the graves, people might be like, “What are you doing?” So I would walk around pretending to be cleaning up the trash. (Laughs)

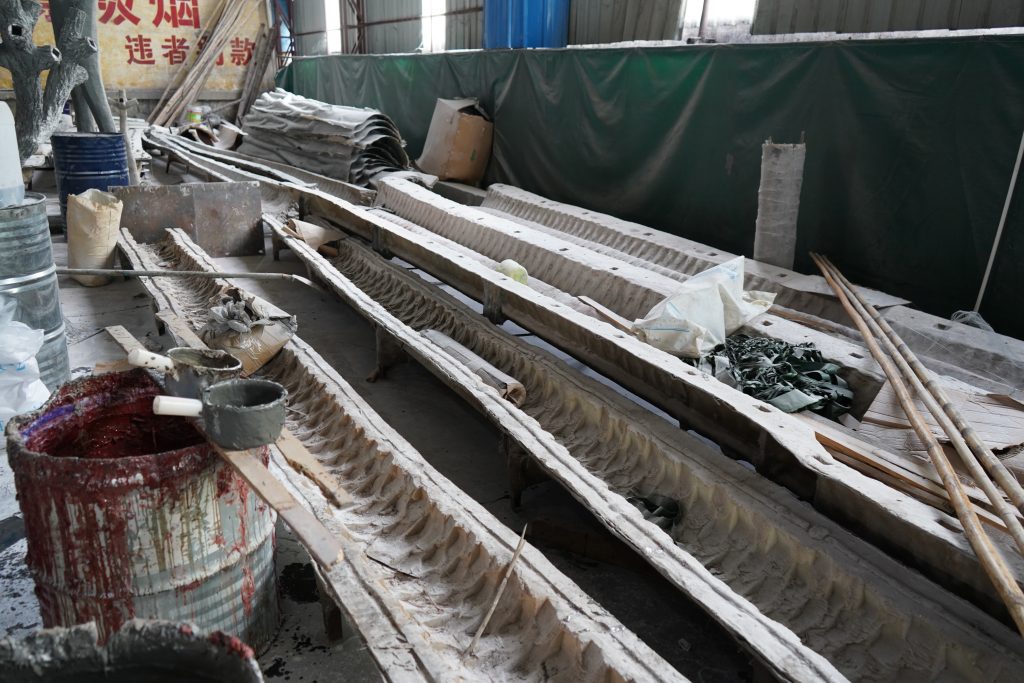

You also visited a factory in Guangzhou, China that manufactures artificial flowers.

I had seen somewhere that “about 90% of the world’s artificial flowers are made in China,” and when I looked up artificial flowers on Alibaba.com in China, I found out that most of the suppliers and factories were in Guangzhou. So I explained the concept to the factories through Alibaba, but in the end, I couldn’t really convey my intentions in English… The factory thought that I was an artist coming to look for decorations to open my own jewelry store, so they politely gave me a sales pitch. (Laughs) But thanks to them, I was able to see a wide variety of artificial flowers on the production line inside the factory and in the huge showrooms. I was also able to interview some of the factory workers over lunch about their living conditions, so I incorporated some of that into the book as well.

Artificial flowers are very convenient for human beings because they do not need to be taken care of, and only the functions of color, healing, and glamour are left. The absence of natural plants and trees is the reason why artificial flowers are so sought after, and when you find them in unexpected places, it makes you feel sad about human greed…

“The diversity of anthropophyta has developed to meet the needs of humanity.” Is there any relationship between the demand for artificial flowers and the social conditions of the place? For example, I heard that you are currently receiving a lot of orders from Middle Eastern countries.

That’s right. In the Middle East, especially now that there are more and more large shopping malls, there seems to be a lot of orders for large palm trees and other indoor decorations. One of the most obvious reasons for the increase in orders for artificial flowers in the Middle East is the climate. Even if the plants don’t grow locally, for example, many “cherry trees” are being made that are bigger and have a different form than the original cherry trees. The palm trees were also much taller than they should have been, and the leaves were smaller and less in proportion to the overall height, creating an unbalanced shape.

In this way, the shape of a plant is adapted by human needs. Human desires and arrogance, such as “I want it to be taller” or “I want the flowers to be more pink,” are expressed in shape and color. In the office of a Chinese artificial flower company I visited, there were artificial flowers with added functions that could be called secondary products, such as a palm tree with more light bulbs coming out of it, or a fountain. They were such interesting and mysterious tools that I wanted to create a project with them.

Rather than using her works to educate people about environmental protection, Honda doesn’t place “artificial” and “nature” on opposing axes. For example, she admires artificial stones as a beautiful material, and she has created an illustrated book based on the assumption that artificial flowers are recognized as an ecosystem.

I did not originally create this work with environmental issues in mind. Rather, I was conscious of “how to make trash interesting,” so I tried not to include such messages. Until now, humans have regarded natural and artificial things as opposites. However, in this era, also known as the Anthropocene, the line between the two is becoming quite blurred, as I have been thinking since I saw a stone called “plastiglomerate” (*) found in Hawaii. The plastic has already returned to the soil and is mixing with natural objects to form new “natural” objects. Rather than wanting to convey a message as an artist, I want to work from the standpoint of an archaeologist or an archeologist who records such phenomena from a bird’s eye view, and that is why I borrow the form of fiction and express myself with botanical illustrations and stones.

※A new type of rock, found in 2014, formed when plastic burns.

photographer: Chizu Takakura

I guess I’m just an observer.

That’s right. I believe that by taking a bird’s eye view, we can see the value of things in a flat way. Throughout history, human beings have always given monetary value to limited items such as precious metals and jewels. However, in this world full of various materials and substances, there should be more diversity in the objects that should be given value. By placing a flat value on various materials and substances on the same playing field, our sense of value will be enriched and the brakes will be applied to the unbalanced and excessive exploitation of limited resources. I guess you could say that I am gently questioning the existing value system.

Recently, I’ve been particularly interested in artificial materials that have the appearance of natural products, and I would like to look behind the scenes and into the history of the production of such materials. Fakes are inferior in value to the real thing, but the “effort to make them look like the real thing” should be an added value, and I have come to believe that there are situations where a new “real thing” is created in the process of making fakes. Even in the case of artificial flowers, errors made by human hands can produce interesting effects, and products derived from artificial flowers, such as the lighting added to palm trees, are born.